Project management is a critically important activity for most organisations in

increasingly turbulent times. Organisations have to manage significant change

initiatives with respect to new product introductions, technology upgrades and

revision of working practices as a result of business process re-engineering

evaluations.

The significance of this topic is recognised in Paper P3, Business Analysis with

an entire section devoted to project management issues. Given the multiple

constraints of scope, time and cost (Section F1 b), which must be reconciled

by a project manager, there are many areas of potential conflict that can

threaten the success of a project. Setting the scope of a project is a key activity

for the project manager at the outset as different parties will have different

priorities for a project.

Managing the potential external conflict between stakeholders requires high

order negotiating skills to ensure that there is effective commitment to the

project. Ensuring that projects are delivered on time and within budget will

require the project manager to be able to identify and manage internal (team)

conflict (Section F3 c and d) that can arise when projects extend over lengthy

periods of time and where team members have potentially conflicting demands

to satisfy.

Accountants in their role as department/section managers, or in the specific

role of project manager, need to be skilled at managing conflict. It is widely

accepted that an effective manager must use a mix of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ skills to

promote team working to achieve desired outcomes. Mintzberg’s (1973)

classification of 10 managerial roles is widely accepted as a useful framework

for analysing managerial work. He grouped the 10 roles under the following

three headings:

· Interpersonal roles: figurehead, leader, liaison

· Informational roles: monitor, disseminator, spokesman

· Decisional roles: entrepreneur, troubleshooter, resource allocator,

· negotiator.

Accountancy training is particularly strong in supporting the informational/

decisional roles while the interpersonal roles (plus negotiation) are more

difficult to address in the context of conventional approaches to study and

professional exams. Team leadership and relationship management,

particularly learning how to use conflict to build a team rather than to tear it

down, is a subtle skill that can be developed with observation and practice in

everyday work situations. Observing how project teams work, and particularly

the role of leader, is a very fruitful arena to consider such issues.

Potential conflict exists within any department but become particularly acute

in the area of project management, which involves bringing together individuals from different departments. The project leader in this situation has four additional pressure points that can promote conflict:

· The staff they manage are assigned to the project on a part-time basis

and have responsibilities to their ‘home’ departments, giving rise to

conflict of work schedules.

· Team members bring different skills and there may be different levels of

participation and contribution among team members.

· The different specialists bring their different perspectives, which may not

be compatible with each other.

· Different individuals may be receiving different rewards, reflecting their

positions within their home departments rather than their specific roles

in the projects.

Such difficulties are exacerbated by the fact that the project manager cannot

have superior knowledge of all areas of specialism within the team. As a

consequence, they cannot rely on expert and position power in leading the

team. The project manager has inevitably the problem of managing the

potential destructive conflict that situation can cause while promoting

constructive conflict. Destructive conflict can impede effective performance

and can involve either too much or too little conflict. Too much destructive

conflict divides a team, deepens differences, destroys relationships, motivation

and morale and distracts the team from critical issues. Too little conflict tends

to produce complacency and the avoidance of risk taking and innovation.

The aim of the project manager must be to promote constructive conflict that

helps to clarify problem situations and potential solutions and opens up new

ways of thinking and doing. Where conflict is recognised and effectively

managed further significant benefits arise from the development of team

cohesion, richer communication, team member engagement and a sense of

achievement and success.

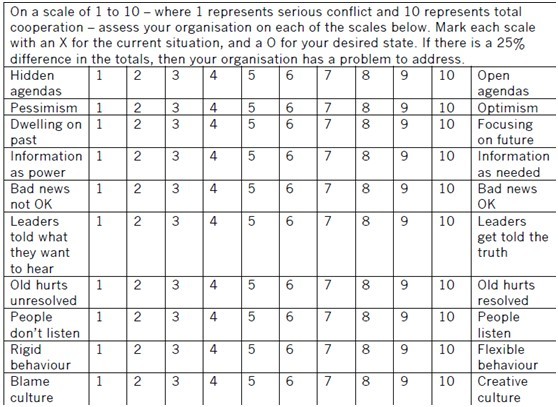

Given the potential benefits of effective conflict management, project managers need to be able to recognise and diagnose conflict situations. Brooks (2001) has developed a useful analytical tool for assessing whether team conflict is being approached positively or is becoming unhealthy. His original proposal viewed the analysis being done at organisational level, but it seems equally applicable to a project team situation. It can be used to open up a dialogue regarding this critical issue among team members. Brooks distinguished 10 features of group behaviour (see Table 1 below) that are assessed at two levels: a) the current situation; b) the desired situation and where there is a 25% difference between the total scores for each of these assessments – Brooks would argue that conflict resolution activities need to be instigated.

If issues are left unaddressed, Brooks argues that a downward spiral in relationships will build its own momentum and is unlikely to get better without positive intervention.

Table 1 – Evaluation of group behaviour and potential conflict in a group

As in many situations, a procedure that identifies the symptoms of a problem is also indicative of the areas requiring resolution. For example, if the above analysis were to be applied and the two areas of greatest divergence between

current and desired situations were on the scales of pessimism – optimism and

dwelling on the part – focusing on the future, these aspects of group behaviour

would need to be the subject of open and frank discussion within the group.

This is easily said but difficult to achieve and Brooks advocates the use of

expert, third party facilitators; however, in many situations, this is not a viable

option. In consequence, the project team leader will need to consider how a constructive dialogue can be initiated to understand different viewpoints in the

group. This is likely to involve the following three stages.

1. Allowing individuals to share their viewpoints. The point at this stage is

for people to hear and understand each other, without assessment of

‘right’ or ‘wrong’.

2. Having allowed everyone to ‘voice’ their viewpoint, there is a need to

generate some shared understanding as to possible ways in which things

could be improved. The focus must not be on who is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’

but on the future and how things can be improved.

3. Ideally, discussion should lead to practical outcomes in terms of how

future disagreements should be handled and how current working

practices might be changed.

In the above context, one can recall Pascale’s (1982) view that conflict

management is built on the principle that ‘individuals should be allowed to

disagree without being disagreeable’, and it is only through such processes

that mutual respect can be developed, the cornerstone of effective team

working.

This is a considerable challenge for managers, and formal training in these

skills is obviously beneficial since, once mastered, they will be of ongoing value throughout an individual’s career.

Dr Graham Morgan is senior lecturer of management and strategy at

Birmingham City University Business School

References

· Brooks M (2001), How to resolve conflict in teams, People Management

(August), Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development

· Mintzberg H (1973), The Nature of Managerial Work, Harper Row

· Pascale R and Athos AG (1982), The Art of Japanese Management,

Allen Lane

精品好课免费试听